“History never really says goodbye. History says, see you later.”

— Eduardo Galeano (2013)

De senaste 20 årens trend med persistensstudier har fått ett par översikter och jag har redan bloggat om den av statsvetarna Cirone och Pepinsky (2022). Här ska det istället handla om den översikt som ekonomisk-historikerna Leticia Arroyo Abad (CUNY) och Noel Maurer (GWU) publicerade förra året i Journal of Historical Political Economy. Om Cirone och Pepinskys studie var beskrivande till positiv, så utgår Abad och Maurer från vad de kallar en "hälsosam skepticism". Cirone och Pepinsky diskuterade metodologiska och analytiska problem och utmaningar i litteraturen, men betonade, kan man nog säga, möjligheterna: Abad och Maurer belyser mer vad persistensstudierna missar, tar ett bredare perspektiv, inte så mycket på persistensstudiernas egna villkor som Cirone och Pepinsky gjorde.

Abad och Maurers sätt att introducera persistenstemat och -forskningen är intressant! De utgår från institutionell teori:

"Social science assumes the persistence of human institutions. Rules that can change suddenly and randomly are no rules at all. For example, a constitution cannot shape political behavior if politicians can change the procedures that govern lawmaking at their whim. Studying institutions, therefore, means studying the conditions under which institutions are stable and the conditions under which they change. This realization, of course, dates back at least to classical Marxism in which history is seen as a progression from one equilibrium to another, with persistence within the stages. Douglass North’s seminal work (North, 1991) took this insight but removed the teleological elements and proposed a framework to explain how institutions might change — slowly! — over time. As economists and political scientists turned their interest towards the study of institutions, they inevitably began to ask questions about how institutions originated and why they change." (s. 33)

Medan Cirone och Pepinsky började sin diskussion av persistensstudier med AJR (2001, 2002), börjar Abad och Maurer med AJR:s omedelbara föregångare, Engerman och Sokoloffs jämförelse mellan Sydamerika och Nordamerika utifrån en analys av skillnader i vad för koloniala institutioner som skapades på de två kontinenterna. Hos Engerman och Sokoloff ledde olika klimat- och odlingsförutsättningar i Nord och Syd till att olika grödor odlades av kolonisatörerna i Nord och Syd, och att vissa grödor men inte andra odlades med slaveri, vilket genom slaveriets långsiktiga negativa effekter gjorde att dessa regioner idag är fattigare än de vars klimat och jord inte lämpade sig för bomull eller socker. "This line of inquiry was not new, but it led to the emergence of the modern persistence literature", säger Abad och Maurer och menar att AJR (2001) egentligen lade fram en ny version av Engerman och Sokoloffs hypotes. Hos AJR var det inte lämpligheten för vissa grödor som var avgörande, utan förekomsten av tropiska sjukdomar på 1500-1600-talen som gjorde att de europeiska kolonisatörerna valde att regera vissa regioner avlägset (och starkt ojämlikt) men andra med större delaktighet vilket gav bättre utveckling på sikt. Steg tre i persistensstudiernas utveckling var enligt Abad och Maurer att forskare insåg att om man ville mäta effekterna av "bra" och "dåliga" institutioner så skulle man få problem med att jämföra länder som i övrigt är olika, och då började forskarna istället använda mått på inom-statlig variation: mellan socknar, distrikt, valdistrikt etc. På 2010-talet tog det fart, men inte så mycket i ekonomisk-historiska tidskrifter som i nationalekonomiska. På 00-talet var bara runt 5 procent av historiska artiklar publicerade i NEK-tidskrifter persistensstudier, men på 10-talet snarare 15-20 procent.

Joachim Voth (2020) har delat in persistensstudierna i två typer: "apples to oranges"-studier som förklarar ekonomiska utfall idag med icke-ekonomiska orsaker förr, och "apples to apples"-studier som förklarar icke-ekonomiska utfall idag med icke-ekonomiska orsaker förr. Abad och Maurer går ganska rakt in på sin kritik:

"One problem with “Apples to oranges” papers is that the mechanisms are often ill-defined or ad hoc. As a practical matter it is extremely difficult to publish a paper that finds that a major historical event had no effect decades or centuries later. The lack of clear historically-grounded mechanisms, combined with publication bias, opens the possibility that the literature is leading us to believe that there is more persistence than actually exists. Publication bias means that persistence studies are already biased towards false positives. But without clearly-specified and historically-sound mechanisms, the scales

will be weighted even further towards misidentifying spurious correlations and overstating the actual degree of persistence." (s. 34-35)

Det låter som en helt korrekt bedömning. De har också specifika invändingar mot "apples to apples"-studier: hur vet vi att t ex tiden som en polsk by spenderade under ryskt styre påverkar väljarpreferenser mer, eller per capita-inkomster mer? Som Voth klargör är de kausala kedjorna också komplexa och blandar in en mängd variabler: "Does the history of Russian rule in Polish villages influence voting patterns through per capita income? The results of such studies can be hard to interpret unless the mechanisms are extremely well-specified." (s. 35)

Jag gillar väldigt mycket hur Abad och Maurer tänker på persistensstudier och vad de egentligen säger som fält. På ett sätt, säger de, är varje persistens-studie också en anti-persistens-studie: att händelse eller chock X år TX har en idag mätbar effekt, innebär ju att de institutioner som rådde år TX-1 avskaffats. Om koloniala institutioner bestämmer den ekonomiska utvecklingen, så betyder det att för-koloniala institutioner inte spelar roll på sikt, inte har persistens.* Ett annat exempel är Alesina och Fuchs-Schündelns (2007) artikel där de menar att DDR formade sina medborgares politiska preferenser på ett beständigt sätt, så att de en gång bodde i DDR även idag är mer positiva till statlig omfördelning etc än de tyskar som en gång bodde i BRD. Detta implicerar att det kvasi-sovjetiska styret i DDR formade folks preferenser och att preferenser från före andra världskriget alltså inte är persistenta, inte har ett eko idag.** Att jämföra BRD och DDR har också gjorts i en rad andra studier: om tillit, om attityder till migration idag, etc. Det finns också en motsatt studie, som betonar skillnaderna före Tysklands delning: Fritsch och Wyrwich (2016) menar att entreprenörskapet redan 1925 var starkare i det som tjugo år senare blev BRD, än i de regioner som blev DDR.

Ett annat sätt att hitta en "treatment", säger Abad och Maurer, är att använda de tämligen godtyckliga koloniala gränser som europeiska kolonisatörer gjorde. Cogneau och Moradi (2014) använder t ex uppdelningen av Togoland efter första världskriget för att studera effekterna av engelsk och fransk utbildningspolitik. Miguel (2004) använde den godtyckliga, rätlinjiga gränsen mellan Kenya och Tanzania för att studera statsbildning och identitet, och fann att tanzanisk politik lyckades överkomma förexisterande skillnader. I en europeisk kontext fann Backhaus (2019) ett liknande resultat i Polen: 1911 fanns där stora skillnader i utbildning mellan områden under rysk, österrikiskt eller preussiskt styre, men skillnaderna hade minskat 1931 och försvunnit 1961. Abad och Maurer sammanfattar: "In short, the arm of history may be long but it is not always strong." (s. 38)

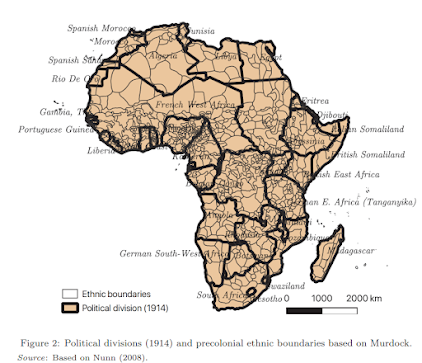

Sektion två handlar om var ens historiska data kommer ifrån, och deras problem. Många persistensstudier av Afrika har utgått från den geografiska fördelningen av etniska grupper före koloniseringen för att kunna studera effekter av kolonialism och slavhandel på senare politiska och ekonomiska utfall. Man har ofta förlitat sig på antropologen George Murdock som 1959 publicerade en studie av etniska grupper i Afrika: kartan ovan, från Nathan Nunn, bygger på Murdock. Så här karakteriserar Abad och Maurer mottagandet av Murdocks studie när den kom:

"The volume was described as “courageous”, “bold”, “influential”, “tour de force”, “provocative” but also “a special menace,” “dogmatic,” and “factually wrong.” The volume was criticized widely and harshly by linguists, historians, and anthropologists in terms that make an economics seminar seem warm and welcoming. Murdock cherry-picked work by botanists, creatively massaged demographic evidence, ignored historical work, disregarded post-war censuses, and contradicted anthropologi-

cal findings. Nor did he make it easy to dispel doubts about factual errors, generalizations, and selective use of sources as his book did not provide a comprehensive discussion of his sources — or even any footnotes at all." (s. 39-40)

Abad och Maurer citerar också en mängd kritiker på olika punkter; de drar inga uttalade slutsatser om implikationerna för de många persistensstudier som använt Murdocks data, men man kan nog läsa in att de är kritiska. De pekar också nöjt på att statsvetaren Paine (2019) tagit fram ett eget dataset för att konkurrera med Murdock.

I studier av Latinamerika har en mängd studier använt befolkningstäthet före Columbus och kolonisatörernas ankomst som en oberende variabel som formar en rad utfall idag: utbildningsgrad, inkomst per capita, tvångsarbete, ekonomisk utveckling, osv. Här finns det en mängd mätproblem:

"The problem is that estimating historical population figures for Latin America is a highly uncertain process at best, due to the lack of pre-Columbian records and the post-contact demographic collapse. The most common technique is to backcast from early colonial population counts. Doing so, however, requires an estimate of the rate of depopulation during the first century after the conquest. Estimations of that rate, however, are all over the map. For New Spain, “High Counters” assumed that the depopulation rate was over 90%; “minimalists” ran with a rate around 20%. These problems are compounded when scholars attempt to estimate the population of geographic units smaller than Viceroyalties. While we can connect different indigenous groups to historical geographical entities, the actual boundaries of these entities are blurry and do not correspond to the eponymous modern units. Compounding the problem, indigenous groups did not respect contemporary political borders. Any estimate of pre-Columbian population densities linked to a particular modern political unit embeds an army of assumptions." (s. 41)De konkretiserar med en diskussion av Argentina och vad för data som egentligen finns där om befolkningstätheten under den förkoloniala perioden.

Den tredje sektionen handlar om de kausala mekanismerna. När jag läste Cirone och Pepinskys översikt över persistensstudierna blev jag lite förvånad över hur enkelt de lät persistensstudier komma undan utan att kunna förklara vilka de kausala mekanismerna är som länkar avlägsen orsak år T med samtida utfall år T+500. Abad och Maurer är mer ense med mig:

"Persistence studies need a convincing mechanism to explain what stops the effects of past events from dissipating. After all, people move, institutions change, and borders shift. Without mechanisms what you have is quantum persistence: spooky effects at a (temporal) distance.De diskuterar tre slags studier som misslyckas med att presentera övertygande kausala mekanismer. Den första är en studie som förlitar sig på en teoretisk modell för att beskriva en hypotetisk mekanism, utan att ge historiska belägg för att mekanismen faktiskt fanns i verkligheten. En annan blandar ihop alternativa utfall med belägg för historiska mekanismer. En tredje presenterar plausibla mekanismer "but tortures history in the process". Som exempel på typ ett ger de Ashraf och Galors (2013) i sanning långsökta argument om att det är vår genetiska diversitet, som varierar mellan länder och regioner idag beroende på vad som hände under homo sapiens uttåg ur Afrika för ca 120 000 år sedan, som bestämmer variationer i ekonomisk utveckling i världen idag.

Mechanisms can take multiple forms. To give a few examples, institutional inertia, cultural transmission, and (used loosely) agglomeration economies have all been proposed as plausible mechanisms. The question is not whether mechanisms are needed. Nor is the question whether such mechanisms can be demonstrated to be the only mechanisms that could explain persistence. Rather, the question is whether the proposed mechanisms will be well-specified and historically-grounded or vague and ahistorical." (s. 43)

"Nonetheless, it remains unclear how genetic diversity translates into economic development. After all, human beings do not directly observe genetic diversity. Rather, people observe phenotypical variations, linguistic differences, ethnic fractionalization, or religious diversity. The evidence that genetic diversity produces differences that humans will care about comes from theory and animal studies. There are alternative explanations for their results — that they have identified a genetic pattern in Europe and East Asia, which also happen to be the most densely-populated places in 1500 and the richest parts of the world today. In addition, their mechanism, if correct, generates implicationsAbad och Maurers bedömning verkar rimlig, och i en fotnot refererar de också till kritik från d'Alpoim Guedes et al (2013) om dataproblemen i Ashraf och Galors studie, och Gelmans (2013) "delightfully brutal take down of a prestigious paper that the author considered silly."

that are not obviously plausible. Would reducing Ethiopia’s genetic diversity (presumably without changing anything else about the country) really lead to economic development? Would encouraging (say) Ethiopians to migrate to Bolivia automatically do the same? The best that can be said about the long-term influence of genetic diversity on growth is that old Scottish adage: 'not proven.'" (s. 44)

En annan studie på mycket lång sikt, om än inte lika lång som Ashraf och Galors, är Com et als (2010) “Was the Wealth of Nations Determined in 1000 B.C.?” De använder Atlas of Cultural Evolution för att koda ifall en region använde en viss teknologi år 1000 f Kr, år 0, och år 1500 e Kr. De använder data om var dagens befolkningar i olika länder kommer ifrån ursprungligen, alltså deras etnicitet, och menar att om land X idag har stor andel befolkning från region Y som år 0 använde en viss teknologi, så är det mer sannolikt att land X idag är rikt. Liksom med Ashraf och Galor är Abad och Maurer inte helt nöjda:

"One problem, however, comes from the fact that Putterman and Weil [om dagens länders befolkningars etniska ursprung] measure only post-1500 migrations. It is unclear, then, why the level of technology used in (say) Iberia in 1000 B.C. should determine technology use in 1500, given that few of the inhabitants of Iberia in 1500 descended from people who were there 2,500 years earlier. Nor should path dependence be accepted without some historical evidence that it operated: there are numerous historical episodes of catch-up in which societies quickly adopt innovations developed elsewhere. In addition, their sources and coding are heavily weighted towards technologies used in

Western Europe." (s. 45)

Ännu lite kortare lång sikt jobbar de studier med som följer Engerman och Sokoloff i att studera effekter av kolonialismen i Amerika. Dessa studier följer E och S i ämne, men använder mer finfördelade data och kollar på variationer inom länder.

"The most ambitious of these papers, Bruhn and Gallego (2012), classify contemporary subnational jurisdictions in terms of a combination of their pre-Columbian population density and their primary economic activities during the colonial era. They divide colonial activities into three categories:

good, bad, and ugly. Good places have no labor exploitation, bad places exploit native and “imported” labor, whereas ugly places exploit local labor simply because there is a lot of labor there to exploit. They then link these colonial institutions to modern economic outcomes. Their coding algorithm

produces some odd results. For example, Virginia and North Carolina are classified as “good,” which is bit puzzling in light of the savage slave systems that characterized both states during the colonial period. Similarly, Missouri receives a rating of “bad,” even though the first plantations did not appear in the state until it became part of the independent United States." (s. 46)

Bruhn och Gallego (2012) visade att regioner med vad de kallade "dåliga" institutioner på 1600-talet var fattigare idag, och de med "bra" institutioner är rikare idag. Det finns dock några undantag, menar Abad och Maurer: norra Mexiko och sydöstra Brasilien hade dåliga institutioner på 1600-talet men är relativt rika, medan det omvända gäller för norra Amerika.

"The conceptual problem with Bruhn and Gallego (2012) is that they do not identify the mechanisms which transmitted the effects of colonial activities to the year 2000. Rather, they confound outcomes for mechanisms. For example, they show that “bad” colonial activities in a region are correlated with modern-day under-representation in the lower house of the legislature. The problem is that modern-day under-representation cannot be a direct cause of modern-day lower income levels. Rather, the cause would be past under-representation that slowed past growth, leading to lower income levels of today. Their mechanism is plausible — although it is unclear why they only consider the lower house

in bicameral systems — but undemonstrated." (s. 46)

Dell (2010) är ett Latinamerika-papper som jobbar seriöst med mekanismerna. Dell utforskar effekterna av mita-institutionen, en form av tvångsarbete som spanjorerna använde för att driva silvergruvorna i Potosí.

"The proposed mechanisms were the system of land tenure, the provision of public goods, and market participation. The paper is meticulous and very well done, but the proposed mechanisms are somewhat questionable, historically speaking. It is not clear that the mita in its classic form persisted for very long. Historians have shown that the mita obligation changed over time. Indigenous populations challenged the institution by buying-out the obligation, baptizing children as females, and mass outmigration. As a result, the mita in 1700s was a very distant cousin to its form in 1578 (Abad and Maurer, 2019).Abad och Maurer är inte övertygade av Dells påstående, grundat i historisk litteratur, att haciendorna utgjorde en konkurrent till den koloniala staten och dess mita vad gällde att rekrytera arbetskraft; A och M menar tvärtom att haciendorna ibland fungerade som arbetskraftsförmedlare till statens gruvor. A och M menar också att böndernas motstånd mot haciendornas expansion in i tidigare mita-områden efter Perus självständighet, visar att haciendorna inte var så mycket bättre som arbetsgivare än vad gruvorna var, som Dell menar och förutsätter. A och M ifrågasätter också de mekanismer genom vilka haciendorna enligt Dell sedan främjat tillväxt: investeringar i vägar och skolor.

Dell’s primary mechanism relies on data showing that large-scale plantations (haciendas) became more common outside the mita catchment area. Dell posits that haciendas were good for economic development through three channels. First, they protected peasants from colonial exploitation. Second, after independence haciendas saw more productivity growth than non-haciendas because they enjoyed more secure property rights. Third, after independence haciendas were better able to mobilize for public investment in roads and schools. The causal mechanism therefore depends on two claims: (1) the Crown discouraged hacienda formation in mita areas; and (2) at least one of the three aforementioned channels operated after independence." (s. 47)

Från Dell går de vidare till Banerjee och Iyer (2005) som också de ställer frågor om vilka effekter extraktiva koloniala institutioner har på ekonomin på lång sikt.

"They ask whether the colonial landlord system in British India had long-term effects. Under the landlord system, the British placed the local tax liability for a village or group of villages with a single person. The landlord, in turn, received the right to collect taxes from the occupants under his jurisdiction, subject to some legal protections. Independent India abolished the system in short order, unsurprisingly. After demonstrating a causal relationship between being under a landlord and outcomes over the next few decades, they proceed a bit like Sherlock Holmes, eliminating plausible mechanisms until one is left: a polarized and conflictual political environment created by peasant “memories of an oppressive and often absentee landlord class” (Banerjee and Iyer, 2005, p. 1210). Similarly, Iyer (2010) finds that whether an area was under direct or indirect British rule before independence has a persistent effect on the provision of public goods decades later, paying careful attention to the historical plausibility of the proposed mechanisms." (s. 48)En tredje studie om detta är Acharya, Blackwell och Sens (2016) studie om slaveriets långsiktiga effekter i USA. De menar att i counties med fler slavar utvecklade de vita starkare rasistiska attityder, och dessa attityder har därefter överförts från generation till generation, så att counties med mer slaveri på 1850-talet ännu idag är mer rasistiska. Detta är en ganska rolig kommentar i förbifarten, som ändå är rätt fundamental: "Of course, the effect they find is marginal: anti-black attitudes spread throughout the nation and emerged in the North as well." (s. 49)

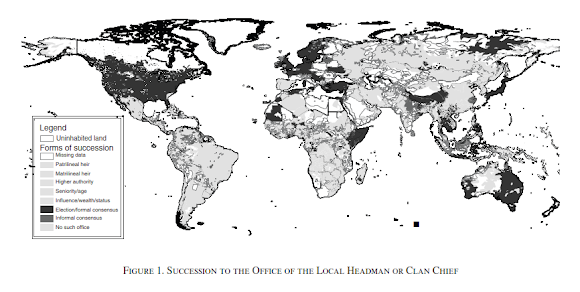

En rad andra studier har också byggt sin mekanism på kulturell överföring från generation till generation:

"Voigtländer and Voth (2012), for example, showed that medieval pogroms in Germany correlated geographically with multiple measures of anti-Semitic oppression and hostility after World War I: Nazi vote shares, anti-Jewish riots, the share of Jews sent to the camps, letters to Der Stürmer, and attacks during Kristallnacht in 1938. As would be expected from a model of cultural transmission, the association weakens with higher levels of migration and in the Hanseatic trading cities, whose economic base required a modicum of tolerance to function. Jha (2013) shows that medieval Indian trading cities, like the Hanseatic League, were far less likely to experience intercommunal violence in 1850–1950, an effect which continues after independence in weakened form. The mechanism is the existence of intergroup complementarities: that is, patterns occupational specialization by ethnicity (enforced and encouraged by community norms) that require intergroup cooperation to function. He carefully uses history to establish the existence of such institutions historically; he then uses 2005 household data to show that attitudes consistent with the mechanism have survived. The fact that his postulated effect survived for so long but weakened over time adds to the credibility of the results." (s. 49)

Chen et al (2020) menar att regioner i Kina med en tradition av att göra det kinesiska rikets examina idag har en starkare utbildningskultur: "They postulate that the need to pass the exams created pro-education traditions among elite families, which in turn passed those attributes on to their children and grandchildren. They cannot observe intermediate cultural variables, but they can and do observe

intermediate measures of elite social cohesion, which provides evidence for their proposed mechanism." (s. 49)

"Establishing mechanisms may be the next frontier.", konstaterar Abad och Maurer, som sagt lite i kontrast till Cirone och Pepinsky. Till och med Acemoglu själv har i ett medförfattat paper 2020 anmärkt att persistens-idéerna, "ideas based on institutional stasis" blivit väldigt populära trots att institutioner i verkligheten förändras ständigt. Abad och Maurers slutsats för mekanism-sektionen är väldigt rimlig och lovande:

"But we would argue that the primary way forward involved taking history more seriously. Identifying convincing mechanisms implies paying attention of the history “in the middle,” painfully constructing historical datasets, and sweating the details. A greater understanding of historical methods and more

collaboration with trained historians would be invaluable. Persistence studies could thereby both better identify real mechanisms and avoid another of the famous pitfalls in this literature: “the compression of history.” It is to this pitfall that we now turn." (s. 50)

fotnot

* De pekar på att James Robinson, R:et i AJR, förklarat Botswanas ekonomiska succé med förkoloniala institutioner som gjort att landet inte drabbats av de koloniala institutionerna så som AJR (2001) säger.

** Voth (2020) dömer däremot i princip ut Alesina och Fuchs-Schundelns studie; för honom exemplifierar den studien det mer generella problemet med persistensstudier som ignorerar skillnader mellan enheter som föregår "the treatment", i detta fall kommunistiskt styre: "The assumption that assignment to treatment in the past is often as “good as random” is unfortunately often wrong. Implicitly, the Alesina and Fuchs-Schündeln paper assumes that pre-1945, East and West Germany were largely identical in attitudes – and hence, any differences that appear today must be the result of the Communist “treatment”. This assumption is prima facie sensible, in the absence of evidence to the contrary – after all, they had formed part of the same country since 1871. However, there is strong evidence that the area of Germany that became the GDR was already strongly different in a number of important dimensions prior to 1945 – church attendance was already lower, female labor force participation was higher, and electoral support for the Communists was higher in the East in the interwar period (Sascha O. Becker, Mergele, and Woessmann 2020). In other words, the ‘treatment’ of Communist rule and Soviet occupation may only have preserved or amplified pre-existing differences. This does not imply that there was no persistence – it implies that it was so strong in this particular case that even the cultural and social effects of a brutal, long-lasting dicatatorship did little more than to leave intact differences that existed long ago." (Voth 2020, s. 11)

referens

Leticia Arroyo Abad och Noel Maurer (2021) "History Never Really Says Goodbye: A Critical Review of the Persistence Literature", Journal of Historical Political Economy, 2021, 1: 31–68